Making "scary" surgery safe

- Debby Ng

- Jun 13, 2014

- 3 min read

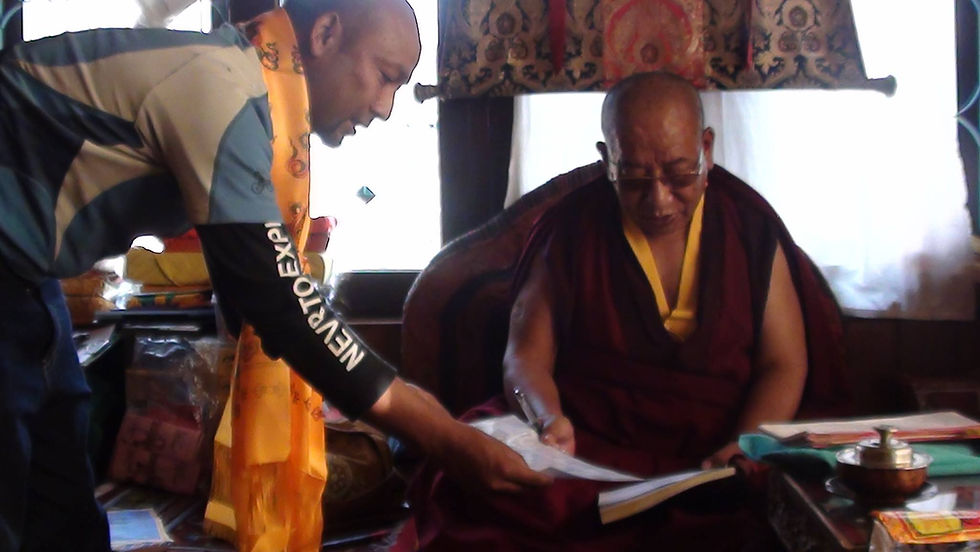

Many of the communities we work with do not have a culture of medicine. For you and I, when we seek medical advice or intervention, we trust the methods because it is something we are accustomed to since young. Many locals we work with are still skeptical about the safety of the neutering procedure. Tackling this challenge is a long term and ongoing effort. (Above: The head monk of Manang, Lama Guru Rinpochi Seruf Gyalzen, has praised and pledged his support for our project! He shared that he is excited to have a project that gives an alternative to the dog culling that has been taking place in the district)

When our team arrived at in the village of Pisang, residents were keen to learn of a method that could reduce the dog population. "Stopping births" sounded like a good idea. But when they realised that the procedure was "more than an injection" and that their dogs would be anaesthetised and operated on to have reproductive organs removed, many felt it was more convenient to not bring their dogs because the idea of it was frightening, they felt their dogs may be unable to recover, or that working dogs wouldn't be able to return to work. Our team of vets and technicians sat waiting for residents of Pisang to bring their dogs to our camp, but they were busy socialising at a religious event that was being held at the local monastery. We saw people sitting alongside their dogs (above) and we silently wished that they would gather their animals to bring them to our neutering camp.

Time ticked away, and we were losing daylight and the warmth of the afternoon sun (that was important for the animals under anaesthesia that would be unable to regulate their body temperature) so my colleague, Mukhiya Gotame, had to think of an idea quickly. He made his way to the village Lama (religious leader), and explained to him the importance of our project. He encouraged the Lama to discuss the details and benefits of neutering and vaccinations with his congregation, and to inform locals about our camp that would be in the village for just two days.

I sat and watched as Mukhiya returned from the monastery. We had done what we could. Now, all we needed was patience. The chime of bells summoned villagers into the monastery. After a series of chants and the sound of the Tibetan longhorn, villagers began to trickle out of the monastery. They sat outside to mingle and sip chai. We sat and watched them anxiously. Then we noticed people gathering their dogs with leashes - an unusual sight as dogs are conventionally left to roam freely. Some people picked up their small dogs and carried them. Mukhiya said quietly, "Now they are coming."

It was a triumphant moment for our team! Our vets put on their gloves and prepared the tables. We were "in business"! Above: A dog owner places his sedated dog onto our preparation table.

Because the local culture of dog ownership does not include medicine or routine care and attention, our team dispensed topical anti-inflammatory ointment to dog owners (Above) and encouraged them to apply it on their dogs for the first two weeks. This was done as a way to encourage dog owners to check on their dogs daily. This simple step, can make a big difference to the recovery process of the dogs and also encourages dog owners to communicate with our team if they spot anything amiss with their animals.

Organising this camp and successfully neutering animals is all well and good, but long term contact with these communities is essential to nurture attitudes of responsible dog ownership, which can then prevent negative interactions between dogs and wildlife. Mukhiya is constantly busy on the ground in Kathmandu and the Himalaya, raising awareness about our project and sharing with others how dog sterilisation can make a huge impact for wildlife and communities. We're thrilled and encouraged to be gaining support from all over the world, but most importantly, from the people of Manang district and the rest of Nepal!

Comments